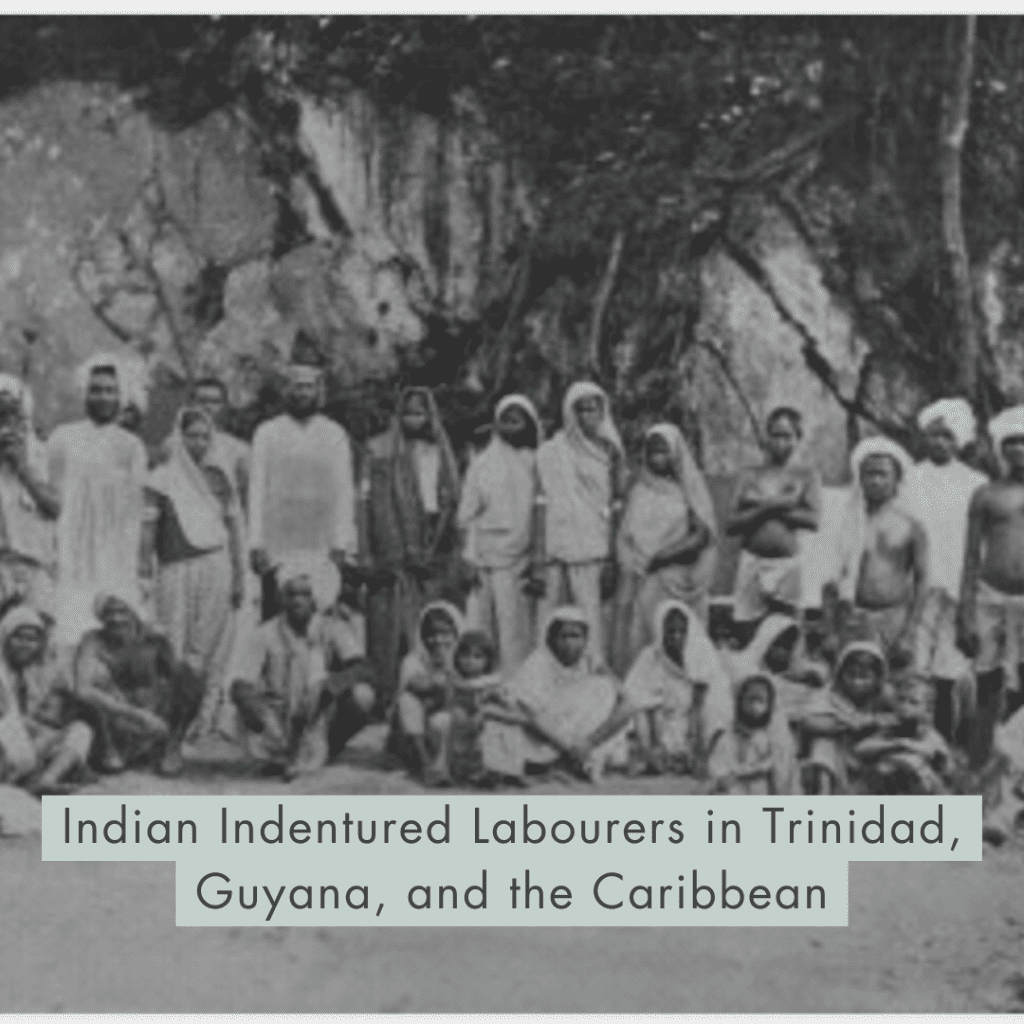

Indian Indentured Labourers in Trinidad, Guyana, and the Caribbean

This article is about Indian Indentured Labourers in Trinidad, Guyana, and the Caribbean.

Introduction to Indian Indentured Labourers in Trinidad, Guyana, and the Caribbean

The history of Indian indentured labourers in Trinidad, Guyana, and the Caribbean is a tale of resilience, struggle, and cultural preservation. I've been researching my family history over the last 7 years and learned so much about Indian indentureship, the Indian population, and the harsh reality of colonial rule by the British government.

During the 19th century, the British Empire sought to address labor shortages in its colonies and turned to countries like India as a source of cheap labour. Through the indenture system, thousands of east Indian immigrants were "recruited" and transported to various British colonies in South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, and the West Indies (including British Guiana, Trinidad, St. Vincent, St. Lucia, and French Guiana). A smaller population of Indians were also indentured in French colonies.

Between 1834 and the end of the system in 1920, it's estimated that over one million Indians were transported across the oceans under the indenture system to toil on sugar, cotton, and rubber plantations. The system, while touted as an ‘opportunity’ for the impoverished from the Indian subcontinent, often involved exploitative contracts and harsh living conditions that were akin to a new form of slavery.

Key aspects of the Indian indentured labourers in Trinidad and the Caribbean included:

- Recruitment: Most labourers, known as "girmitiyas" or "coolies", were often misled with promises of lucrative jobs and better life prospects. Many were not fully aware of the nature of the work, the length of their indenture, or the conditions they would face.

- The Middle Passage: The journey from India to the Caribbean was treacherous, taking several months at sea, with horrendous conditions similar to those experienced during the African slave trade. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and rampant disease contributed to a high mortality rate during transit.

- Living and Working Conditions: Upon arrival, indentured Indians faced long working hours, insufficient food, inadequate shelter, and the constant threat of punishment.

The Background: Abolition of Slavery and the Need for Labour

The abolition of slavery was a pivotal chapter in history, culminating in various legislative acts worldwide. In the British Empire, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 marked the end of slavery. The Act enforced emancipation, which inherently disrupted the labor systems, especially in colonial plantations where the economy heavily relied on enslaved African labor. These plantations in the Caribbean islands primarily produced sugar, an enormously lucrative commodity at the time.

The substitution of indenture for slavery displayed colonial powers' continued dependence on exploitative labor practices. It echoed the maintenance of the economic status quo—essentially replacing one form of bondage with another—while perpetuating the colonial profitability through the exploitation of disenfranchised populations.

Recruiting the Labourers: Promises and Realities

The journey of Indian indentured labourers to the Caribbean began with the deceptive recruitment practices of the British Empire. Labourers were often lured with promises of wealth and a better life. Recruiters, known as "Arkatis" or "Maistris," painted an idyllic picture of life on the sugar plantations, assuring potential indentured servants of favorable living conditions, fair wages, and the opportunity to return to their homeland with their newfound fortunes.

- Recruiters often utilized a mix of incentives and misinformation:

- Prospective labourers were promised manageable work hours.

- There was an emphasis on the availability of land and resources in the Caribbean.

- The journey itself was romanticized, described as traversing oceans for a grand adventure.

- They were also promised free return passage

- Realities of the labourers:

- Upon arrival, the indentured found themselves in harsh plantation environments.

- Long grueling work hours far exceeded what was promised.

- The disparity between low pay and high costs of living led to an inability to save.

- Contractual obligations and penal sanctions made it nearly impossible for many to return to India after their servitude.

Indentured labourers often realized too late that they were trapped in a cycle of labour that bore more resemblance to slavery than the opportunities for which they had hoped. The realities of their existence in the Caribbean stood in stark contrast to the hopeful promises they were given, marking a legacy of exploitation under the guise of economic opportunity.

The Journey Across the Oceans: Conditions on the Voyage

When Indian indentured laborers embarked on the grueling journey to the Caribbean, they faced dire conditions aboard overcrowded ships. Life on the open sea presented a stark contrast to their homeland, with the following aspects characterizing the voyage:

- Cramped Quarters: The ships were often overpopulated, squeezing laborers into tight, unhygienic spaces which led to the rapid spread of disease and discomfort.

- Health Risks: With minimal medical facilities available, common illnesses could quickly turn fatal. Malnutrition and dehydration also posed threats due to inadequate provisions.

- Mental Strain: Aside from the physical hardships, the psychological toll was immense. Many laborers experienced severe homesickness, depression, and anxiety about their uncertain future.

- Violence and Abuse: Instances of violence and abuse were reported, with many experiencing mistreatment at the hands of the ship's crew. The lack of accountability and protection exacerbated these issues.

- Limited Sanitation: Sanitation facilities were woefully insufficient for the number of people on board, contributing to unsanitary conditions that further endangered health.

- Death: The perilous journey claimed many lives. Mortality rates were high, and the passing of fellow travellers added to the somber atmosphere aboard the ships.

These conditions compounded the overall trauma of the indenture system, laying the foundation for a chapter in history marked by struggle and endurance.

Arrival and Adaptation in the Caribbean

As Indian indentured laborers disembarked from the cramped quarters of ships onto Caribbean shores, they were often greeted with an environment both physically and culturally dissimilar to their homeland. The transformation of their lives began instantly as they stepped onto the expansive sugarcane plantations that would become both their workplace and new home.

- The first challenge was the tropical weather; many laborers were unaccustomed to the intense heat and humidity. They had to acclimatize quickly, and this environmental shock was only the beginning of a series of adjustments they would need to make.

- Adapting to the local foods proved initially difficult due to the unfamiliar ingredients and cooking methods. However, over time, Indian indentured laborers in Trinidad and the broader Caribbean began incorporating local produce into their cuisine, resulting in the creation of new, blended dishes that are now staples in Caribbean culinary culture.

- Communication presented initial hurdles due to the language barrier between the Indian laborers and their colonial supervisors. Over the years, this led to the development of a pidgin language, easing communication and leading to the unique linguistic amalgamations still apparent today.

- Adjusting to the societal norms and values of Caribbean culture was another aspect of the adaptation process. This involved learning new social customs, often blending their traditions with those of other ethnic groups on the islands, resulting in a rich cultural tapestry.

The first British colony to receive Indian indentured servants was Mauritius. On November 2, 1834, the Atlas arrived in Mauritius. This day is now honored as Aapravasi Diwas. ("Under the French rule, in the year 1729, the first Indians were brought to Mauritius from the Puducherry region, to work as artisans and masons.") https://hcimauritius.gov.in/pages?id=9avme&subid=yb8md&nextid=RdG7d#:~:text=Mauritius%20is%20a%20former%20British,work%20as%20artisans%20and%20masons.

Many other colonies also commemorate the first ship that brought Indian indentured labourers to the land.

- November 2, 1834 - Mauritius

- May 5, 1838 - Guyana

- May 10, 1845 - Jamaica

- May 30, 1845 - Trinidad and Tobago

- October 27, 1848 - Belize

- December 24, 1854 - Guadeloupe

- May 1, 1857 - Grenada

- May 6, 1859 - St. Lucia

- November 16, 1860 - South Africa

- June 1, 1861 - Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- June 5, 1873 - Suriname

- May 14, 1879 - Fiji

On May 5, 1838, the Whitby arrived in British Guiana with the first set of Indian indentured servants. The first ship carrying indentured labourers to Trinidad, the Fath Al Razak or Fatel Rozak, arrived in Trinidad on May 30th, 1845.

For reference, the last ship arrived in the Caribbean in 1917.

Life for indentured labourers was marked by arduous physical labour on sugar plantations and estates. They endured long hours in challenging conditions, working tirelessly to sustain the British Empire's growing sugar industry. Indian women, in particular, faced unique challenges as they balanced their roles as workers and caregivers, often separated from their children and families.

Life on the Plantations: Hardship and Resistance

Life for Indian indentured laborers on Caribbean plantations was marked by severe hardship. Workers toiled for long hours under the scorching sun, often without adequate nutrition, clean water, or medical care. The labor-intensive work included clearing land, planting sugarcane, and harvesting the crop, which required physical resilience and endurance. It was common for laborers to fall ill due to the harsh working conditions and lack of sanitation.

The overbearing plantation system attempted to control nearly every aspect of the laborers' lives. Housing was typically inadequate, with multiple families crammed into small, poorly constructed barracks. Moreover, their legal status as indentured servants bound them to the plantation, with few rights and little recourse against abuse and mistreatment.

Despite the relentless exploitation, indentured Indians manifested their resilience through acts of resistance. They utilized various methods to oppose their oppressors, including:

- Cultural Retention: They preserved their languages, religions, and customs, which provided a sense of identity and solidarity.

- Escapism: Some laborers would abscond, seeking refuge in the wilderness or neighboring villages.

- Legal Action: Using the limited legal channels available, some challenged their conditions or the terms of their indenture.

- Strikes and Uprisings: Laborers organized strikes and, in some cases, violent uprisings, though these were often met with harsh retaliation.

Their resistance was emblematic of their desire not only for improved working conditions but also for the fundamental recognition of their humanity. Despite the systematic efforts to dehumanize and exploit, the strength and spirit of the Indian indentured laborers remain a testament to their struggle and their yearning for freedom which can be seen throughout the Indian diaspora.

Cultural Preservation and Syncretism

When Indian indentured labourers set foot in the Caribbean, they brought with them a rich tapestry of cultural practices, beliefs, and traditions that were destined to interact with the indigenous Caribbean cultures. This interaction led to the process of cultural syncretism, where elements from different cultures amalgamate to form new cultural expressions, enriched by the plurality of their origins.

Language is a realm that witnessed significant syncretism. The labourers spoke Bhojpuri, Tamil, and other Indian languages, which over time, blended with English, African languages, and Creole patois. This paved the way for a distinctive Indo-Caribbean dialect, embodying words and phrases from multiple linguistic sources.

In the culinary field, the indentured labourers in Trinidad, Guyana, and the Caribbean introduced spices and cooking techniques that were hitherto unknown in the Caribbean. These were combined with local ingredients and methods, leading to the invention of new dishes that have become staples of Caribbean cuisine.

Despite these examples of cultural syncretism, the Indian indentured labourers also made concerted efforts to preserve their ancestral traditions. Festivals such as Diwali and Holi are still celebrated with fervor, traditional Indian garments like saris and dhotis are worn on special occasions, and classical Indian dance forms like Kathak and Bharatanatyam continue to be taught and performed.

Contributions to Caribbean Society and Economy

The contributions of indentured labourers to the Caribbean cannot be overstated. They played a pivotal role in shaping the region's economy, working tirelessly on sugar plantations and coconut estates. Their labor helped sustain the British Empire's colonial enterprises and contributed to the growth and prosperity of the Caribbean colonies.

Furthermore, the Indian indentured labourers left a lasting impact on the demographic makeup and cultural diversity of the region. Today, individuals of Indian descent form some of the largest ethnic groups in countries like Trinidad and Guyana. Their cultural heritage is celebrated through events like Indian Arrival Day, which commemorates their arrival and serves as a reminder of their sacrifices and resilience.

- Economic Contributions:

- Indian labourers provided a critical workforce for the agricultural sector, particularly in the cultivation of sugar cane, which was a cornerstone of the Caribbean economy.

- Through their hard work and expertise, they helped sustain the plantation economies post-emancipation.

- Over time, many Indian indentured servants transitioned into land owners and entrepreneurs, contributing to a more diversified economic structure in their new homelands.

- As traders and business owners, Indians introduced new crops such as rice and contributed to the agricultural diversification of the Caribbean economies.

- Social Contributions:

- The legacy of Indian culture is evident in the synthesis of Indo-Caribbean music, dance, festivals, and cuisine, reflecting their considerable influence on the cultural melting pot of the Caribbean.

- Language and religious landscapes were broadened with the introduction of elements from Hindi, Bhojpuri, and Tamil languages and the establishment of Hinduism and Islam as major religions within Caribbean society.

- Indian indentured labourers also played a role in the education sector, with a focus on literacy and scholarship that benefited not only their community but the wider region.

Their journey, marked by hardship and perseverance, resulted in a transformation of societal norms and contributed to the ethnically diverse mosaic that is characteristic of the Caribbean today. Through their indomitable spirit, the Indian indentured labourers laid the foundation for future generations, significantly shaping the socio-economic trajectory of their adopted homelands.

The End of Indentureship: Legacy and Continuities

The termination of indentureship in the Caribbean was the culmination of years of struggle and advocacy against a system considered as another form of servitude. By the early 20th century, various forces—including changing economic conditions, WWI, the growth of nationalist movements in India, and the critical scrutiny from humanitarian organizations—converged to bring an end to the indentured labor system. One of the main reasons that Indian indentured servitude ended was because the British needed the ships to fight in WWI. The last ships brought Indians to the Caribbean in 1917. The system officially ended in 1920, although its impacts continued to resonate in the lives of descendants.

Despite the ending of formal contracts, the legacy of indentureship is deeply ingrained in the socio-cultural fabric of Caribbean societies. The indentured laborers left a profound impact, infusing the region with their cultural practices, religions, culinary traditions, and languages, thereby enriching the Caribbean multicultural mosaic.

- The descendants of Indian indentured laborers have become integral to Caribbean national identities, often holding significant social, economic, and political positions.

- Festivals originally from India, such as Diwali and Phagwah (Holi), are now celebrated widely, symbolic of the cultural integration experienced over the years.

- Indian culinary influences are seen in Caribbean cuisine, introducing ingredients like curries and cooking techniques that have become staples in the region.

However, traces of the indentureship system's inequities persist, with societal divisions and disparities sometimes along the lines of ethnicity—echoes of a stratified plantation society. The Indian indentured laborers and their descendants faced—and to some extent continue to face—challenges in terms of discrimination and social acceptance.

Nevertheless, the end of indentureship represents a significant historical moment that has paved the way for a more diverse and inclusive society, albeit one that must grapple with the complexities of its colonial past. The legacy of the Indian indentured labor force is a testament to their resilience and the indelible mark they left on the Caribbean cultural landscape.

Struggles for Rights and Recognition in the Post-Indenture Era

Following the abolition of indentureship, Indian laborers in the Caribbean continued to face significant challenges in their quest for rights and recognition.

- They encountered limited access to land ownership due to legislative restrictions and economic barriers.

- Employment opportunities were often confined within certain industries, maintaining the status quo of economic hierarchy.

- Social assimilation proved difficult, with the prevailing narratives often disregarding their cultural heritage.

Laborers who chose to remain on the islands post-indenture sought to establish a socio-economic foothold through:

- Formation of community groups and religious institutions, which provided a support network and a means to preserve their cultural identity.

- Active participation in labor movements that aimed to improve the working and living conditions on the plantations.

- Involvement in politics, initially through organizing and later through direct representation, pressing for policies that were inclusive of their interests.

The post-indenture period saw the slow evolution of self-identity, with the descendants of the laborers gradually becoming integral parts of the cultural and political tapestry of Caribbean societies. This marked a gradual shift from a labor force that was once seen as transient and disposable to a community firmly rooted in the Caribbean, contributing to its diversity and dynamism. The journey to recognition and equal rights, however, was fraught with obstacles, requiring persistent efforts for generations to overcome societal and institutional biases.

Rediscovering Roots: The Modern Connection between India and the Caribbean Diaspora

For many individuals, tracing their family roots and uncovering their ancestral connections to the indentured labourers is a deeply personal journey. Archival records, ship registers, and estate registers serve as valuable resources in piecing together family histories and understanding the experiences of their ancestors. Preserving and documenting these stories is crucial in maintaining a connection to one's heritage and ensuring that future generations can appreciate the sacrifices made by their forebearers.

This diaspora, while markedly Caribbean in culture and spirit, retains echoes of Indian traditions, often evident in linguistic elements, religious practices, and familial structures. These cultural remnants have piqued the interest of younger generations who are curious about their forebears' origins. Engagements have grown through:

- Cultural exchange programs that facilitate a dialogue between the diaspora and individuals in India.

- Initiatives by both Indian and Caribbean governments to strengthen diplomatic and cultural ties.

- Genealogical research facilitated by digital archives and ancestry tracing services.

- Academic and literary works that explore the narratives of Indian indentured laborers.

Compellingly, the global celebration of Indian festivals like Diwali and Holi in the Caribbean islands underscores the enduring connection. Additionally, the thriving Indian film industry, Bollywood, also strikes a chord with the Caribbean people, creating a shared space of enjoyment and appreciation.

This rediscovery process goes beyond mere cultural curiosity, signifying a desire to understand the broader nuances of identity and belonging. By delving into the past, the descendants are enriching the landscape of their own cultural narratives within the Caribbean milieu. The fusion of traditions is not only testament to their history but also a beacon for their future, as they blend the legacy of their ancestors with Caribbean vibrancy.

This article was about Indian Indentured Labourers in Trinidad, Guyana, and the Caribbean.

By Melissa Ramnauth, Esq. | This content is copyright of West Indian Diplomacy, LLC and may not be reproduced without permission.

She runs West Indian Diplomacy, a Caribbean blog aimed at promoting West Indian history and business in the global marketplace. Melissa has been an attorney for over 10 years. She currently focuses on trademark registration, trademark searches, and office actions. She also has extensive legal experience in the areas of trademarks, copyrights, contracts, and business formations. She owns her own Trademark Law Firm that is virtually based out of Fort Lauderdale.

Please Sign Our

Petition to Preserve Our Ship Records

By Submitting this Form

This page may contain affiliate links and ads at no extra charge to you. If you purchase something from these links and ads, West Indian Diplomacy may earn a small commission that goes towards maintaining the website and sharing our history.

Book Recommendations

The First East Indians to Trinidad: Captain Cubitt Sparkhall Rundle and the Fatel Rozack

History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago

An Introduction to the History of Trinidad and Tobago

Legal Disclaimer

Your use of the content on this site or content from our email list is at your own risk. The use of this website does not create an attorney-client relationship. West Indian Diplomacy does not guarantee any results from using this content and it is for educational purposes only. It is your responsibility to do your own research, consult, and obtain a professional for your medical, legal, financial, health, or other help that you may need for your situation.

The information on West Indian Diplomacy is “as is” and makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, with respect to the content provided on this website or on any third-party website which may be accessed by a link from this Web site, including any representations or warranties as to accuracy, timeliness, or completeness. West Indian Diplomacy will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information.

All information on this website is accurate and true to the best of West Indian Diplomacy's knowledge, but there may be omissions, errors or mistakes. West Indian Diplomacy is not liable for any damages due to any errors or omissions on the website, delay or denial of any products, failure of performance of any kind, interruption in the operation and your use of the website, website attacks including computer virus, hacking of information, and any other system failures or misuse of information or products.

As of this date, West Indian Diplomacy does not write sponsored posts or accept free products for review. All thoughts and opinions written by West Indian Diplomacy is our own.

West Indian Diplomacy welcomes comments on blog posts. All comments submitted to us are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies, or positions of this site. We reserve the right to use our own discretion when determining whether or not to remove offensive comments or images.